On most Saturdays, if I’m not too busy with other things, I go to a shop in our village and buy a copy of the Financial Times Weekend. I do this, not because I have any interest in the financial markets but because at the weekend the Financial Times transforms itself into the best UK newspaper in terms of its coverage of things that do interest me – politics, world affairs, the arts, book reviews, gardening etc.

One of the features I always look at is the ‘Inventory” column in the FT Weekend magazine, in which they interview a well-known person and ask them a standard set of 18 questions, eg: What was your childhood or earliest ambition? Private school or state school? Who was or still is your mentor? How physically fit are you? Ambition or talent: which matters more to success? etc. The question I always find myself turning to first of all is: “Do you believe in an afterlife?”

This week the subject was Bobby Gillespie, a musician who co-founded the band Primal Scream in 1982. His answer to the question was: “I don’t. I do believe in a universal energy – we’re all part of each other. We’re just the human race”.

The previous week the interviewee was Kate Clanchy, who is a teacher, writer and poet who was appointed MBE for services to literature in 2018. Her response to the question was: “No. Maybe only a literary afterlife – I think that’s one of the reasons to write. Your words can live on. I believe in the human capacity to remember each other and love each other”.

These two responses are fairly typical of answers to this question. I haven’t kept a tally but my guess is that around 8 out of 10 interviewees say that they have no belief in an afterlife. I find myself vaguely disturbed by these results. Why is it that so many people who are prominent in public and cultural life seem to know so little about the reality of what it is to be a human being?

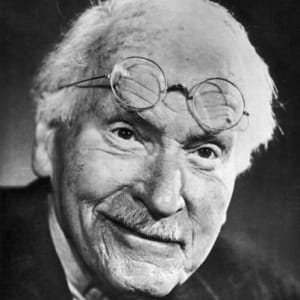

A slightly different question was asked of the great psychiatrist Carl Jung in a TV programme called “Face to Face” in October 1959 when he was interviewed by John Freeman. Jung, who was 84 at the time and was still active in his field, spoke to Freeman about education, religions, consciousness, human nature and his relationship to Freud. When Freeman asked Jung whether he believed in God, Jung’s reply was: “I don’t need to believe, I know”.

Carl Jung

This reply has caused something of an outcry, both at the time and in the years since; in 2006 the biologist and convinced atheist Richard Dawkins accused Jung of “blind faith”. I don’t think this is a fair accusation. Jung had worked hard on himself all his life and had worked extensively with a wide range of patients so could speak with the authority of a lifetime of inner exploration. Four years earlier, in another interview, Jung had expanded a little on this theme: “All that I have learned has led me step by step to an unshakeable conviction of the existence of God. I only believe in what I know. And that eliminates believing. Therefore I do not take his existence on belief – I know that he exists”.

Jung’s view, given in letters after these interviews, is that there is something very real and mysterious, which we all call God, but the images of God we all hold are different and inadequate. He seems to have been suggesting that we should recognise that any and all images of God are always different from the actual nature of God.

In that same interview with John Freeman, Jung said this: “We need more understanding of human nature, because the only danger that exists is man himself — he is the great danger, and we are pitifully unaware of it. We know nothing of man — far too little.” Anthroposophists of course would tend to agree with Jung; but we would also go beyond Jung in our view that we already know quite a lot about what it means to be a human being, not only during our physical incarnations but also in our soul and spiritual natures.

I sometimes wonder what I might reply in the highly unlikely event that I was interviewed and asked whether I believed in an afterlife. I should probably say: “Yes I do, and also in many ‘before’ lives as well as afterlives to come”. But this sort of conviction seems to be uncommon today, when a kind of solipsistic cynicism about anything other than the material is more usual. A quotation from the late, great comic, Peter Cook, sums up this attitude for me: “As I looked out into the night sky, across all those infinite stars, it made me realise how insignificant they are”.

But what would Carl Jung have said if he had been asked about the possibility of an afterlife? Writing in 1934, he commented:

“Critical rationalism has apparently eliminated, along with so many other mythic conceptions, the idea of life after death. This could only have happened because nowadays most people identify themselves almost exclusively with their consciousness, and imagine that they are only what they know about themselves. Yet anyone with even a smattering of psychology can see how limited this knowledge is. Rationalism and doctrinarism are the disease of our time; they pretend to have all the answers. But a great deal will yet be discovered which our present limited view would have ruled out as impossible”.

To my mind, Jung is quite infuriating on this topic – evasive, long-winded and seemingly unwilling to state publicly his private convictions. Jung obviously decided to remain completely empirical in his public observations, confining his work to inner soul images. Jung also speaks of psychoanalysis as the only initiatory path available in the modern Western world.

This is not so, of course, and this is just one reason why for me Steiner is of much more interest than Jung: it is because Steiner has an absolutely clear understanding and knowledge of the transcendent and is able to observe the invisible spiritual realms and report what he has seen. Whereas Jung kept his work firmly in the region of the soul, Steiner was able to develop his capacities of consciousness so as to reveal the nature of the spirit – and to teach how other people can develop these capacities as well.

Rudolf Steiner in 1911.

There is a danger here and that is that Steiner’s teachings, taken on their own, and without any conscious connection to one’s own soul life and inner experience, can lead one to fall into anthroposophy as though it were a religion – which it emphatically is not. Anthroposophy, in fact, is a path of research and hard meditative work leading to various outcomes in consciousness, thinking, feeling and willing. This is quite a tall order for people living in a culture in which materialistic individualism reigns and there is no connection to the collective forces of the soul – but it is a necessary path to take if one wishes to understand the physical-soul-spiritual wholeness of the human being.

Another comic – Les Dawson – possibly not as great as Peter Cook, was asked on his deathbed if he wanted to be buried or cremated: “Surprise me”, he said. So there’s hope yet Jeremy. But then Dawson came from a very different background from Cook.

LikeLike

Thank you – that’s a lovely story, bresbo – it’s almost too good to be true!

LikeLike

I have been buying everyone a copy of “The Afterlife of Billy Fingers” by Annie Kagan. The descriptions of the expansion are the closest thing I have ever seen to Steiner’s. And in a way, It helped me be able to get my head around Steiner’s description a bit better. Awesome book!

LikeLike

I am glad to have found this blog! There are good questions for discussion here. Personally I have benefited greatly from Jungian thought but if I’m in it too long I become dissatisfied. It remains in a realm of analogies and “likenesses” rather than the real thing. But if one isn’t ready to face reality, those images can perhaps be helpful.

Regarding the denial of God and life after death, Helen Keller, a remarkable spiritual thinker, wrote “All denials of God are found at last to be denials of freedom and humanity.” I think that people can’t accept the existence of God because they can’t accept what it means to be a human being, and they’re afraid of freedom. They can’t conceive of an “afterlife” because they don’t live fully in this life; they sense how at the threshold of death, this feeble non-life will be snuffed out. So they are not wrong, in a way.

The people who truly live, in spite of handicaps and limitations, are the ones who know God as a matter of course. We can learn much from them.

LikeLike

Welcome to the blog, Lory!

I, too, have benefited from Jung’s work but after a while feel the need for greater nourishment, which I find in Steiner. Thank you for the quotation from Helen Keller.

I also like this quotation from Francis Bacon’s essay on atheism: “It is true, that a little philosophy inclineth man’s mind to atheism; but depth in philosophy bringeth men’s minds about to religion”. Steiner himself, of course, thought that atheism came from a diseased organism: “Only those human beings…are atheists in whose organism something is organically disturbed. To be sure, this may lie in very delicate structural conditions, but it is a fact that atheism is in reality a disease…For, if our organism is completely healthy, the harmonious functioning of its various members will bring it about that we ourselves sense our origin from the Divine – ex deo nascimur (from God we are born).”

LikeLiked by 1 person

“in christo morimur”? did bacon go there? or, ” in corpus morimur”?

the real issue is “per spiritum sanctum reviviscimus” the risen god, but he is as yet barely perceptible,..

LikeLike

Religion requires belief. Truth requires no proof – it is intrinsic within our very being. “The Kingdom of God is within YOU”. Human language is (very) limited. It attempts to explain what it cannot. Do I believe in an afterlife? That which is within me confirms that yes, there is, was, and shall (always) be.

LikeLike

Great article Jeremy!

Everyone always talks about the afterlife, but of course it’s also a pre-life as well.

I’m in the same camp as Jung. I don’t believe, I know, based on direct empirical evidence. Not every detail but I’ve had enough direct experience that I tend to give Rudolf Steiner the benefit of the doubt as to what he reports regarding extended reality, the big picture.

I enjoy your writings – please keep on sending!

thanks

Martin Stevens (from Peru)

.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Hi Jeremy,

Thanks for the article. I would like to pick up on your quote from Jung saying “I don’t need to believe, I know”.

An underlying mood of our time is that many people don’t want to believe the possibility that others might be able to experience and understand things that they do not experience themselves. To a certain degree this is of course healthy. However arrogance or fear, for example, leads people further – to reject even the possibility that others might experience things that they don’t experience themselves. This rejection is true of many anthroposophists as well as others who profess a spiritual or religious belief and not just the materialist believers like Dawkins. This belief can trap us in materialism as non-material things cannot be simply shown outwardly to others.

Often the more illustrious someone’s position in an organisation the more they don’t want to admit to themselves and others that their perception and insight is not as deep as other, perhaps outwardly more lowly, brethren. It is easier to ignore, cast doubt or criticise and thereby eliminate this possible threat to their role and status. This in turn leads those with genuine capacities and insight to not join, or leave, the organisations that profess, for example, to be a home for spiritual insight. It also leads to a dearth of people with real insight to be the prominent ones in public and cultural life which you point to in your article.

So how can one differentiate between those that claim they know and those that really know? First one has to know oneself well enough to not fall into the trap described above! That path of self-knowledge is the journey we are all on.

My wife Caroline Brown published a book about her journey back in 2015. This may be of interest to some – see http://www.doorwaytohiddenworlds.org/

Thanks Jeremy for your articles and Blog

Stuart Brown

LikeLike

Hello Stuart Brown,

I liked your comment above and look forward to reading Caroline’s book which I have just ordered via the Kindle edition.

I’m guessing you are my King’s Langley classmate who I have not seen since the late 1960’s – Clare Dubrovic was our class teacher. If so do drop me a line at martinstevens@juno.com, I’d love to catch up with you.

I live in the Amazon jungle of northern Peru and have had quite an interesting life since last we met. I have a book out on Amazon (where else given where I live!) called ‘Long Road to Chavin’ outlining some of my adventures.

all the best to you and yours

Martin Stevens

LikeLike

Yes, I do, because without an afterlife consideration of the life just ended, we have no knowledge of how we did. That’s why we obrain a grade

Sent from my iPad

>

LikeLike

A very powerful, existentially significant question, Jeremy.

I believe there is no way to rationally justify one’s own answer, yeah, or nay, to this question. And for me that is one of the blessings of our state as humans, because no one else has justification for saying, ‘I am right and you are wrong’, when it comes to life after death. Jung is bullshitting when he says, ‘I know’. If you asked him how he knew, in the end it would boil down to, ‘I just know’. It wouldn’t stand up in court.

You say, ‘Steiner himself, of course, thought that atheism came from a diseased organism: “Only those human beings…are atheists in whose organism something is organically disturbed. …..’

My initial reaction to this is one of sadness and disappointment.

How glib, I feel, to say that those who disagree with you are ill, or sick, – diseased. This is worthy of Dawkins himself, saying that religious or spiritually minded people are deluded, comparing them to a person with schizophrenia or alzheimers who may have delusions.

The attribution of disease was also used by the east german communists to incarcerate political opponents in secure mental hospitals.

Did Steiner really say, in effect, ‘The thought, ‘There is no God’, must be the product of a diseased organism!’?

I.e. he did not accept that a thinking person might come to such a thought, as a response for example, to seeing the evil that people do in the world. Evil existing apparently without explanation. My son (someone who greatly enjoyed and benefitted from his Steiner education in Kings Langley),would say, ‘If there is a God, a creator of universes , it must be a being without compassion or morality to have created a world where innocents suffer intolerably at the hands of people like Stalin, Mao, Pol Pot, greedy megacorporations, etc, etc. I do not think there is a God. There is no explanation for the suffering in the world except human greed and cruelty.’

I had believed that Steiner respected other points of view, even if he disagreed with them. If you harbour the thought, ‘This person is ill’, simply because they express a point of view that you yourself believe to be wrong, is this respect?. Or are you diminishing that person with whom you disagree. Are you effectively saying,’ No normal or rational person could possibly come to such a view, therefore you are ill’.

I find comfort in the fact that in my experience Steiner is sometimes inconsistent. He is quite capable of appearing to be narrow-minded and prejudiced and elsewhere enlightened and inspired.

I hope you will allow me to quote quite a long passage from ‘The Inner Aspect of the Social question’, which has been an inspiration to me over many years.

‘Thus Christ speaks today to those who hearken to Him,

“In whatever the least of your brethren thinks, you need to recognise that I am thinking in him; and that I am feeling with you, whenever you bring the thought of another into relation with your own thought, whenever you take a social interest in what is taking place in the soul of another. Whatever opinion, whatever outlook on life you discover in the least of your brethren, therein you are seeking Myself” ‘.

Perhaps when Steiner said that atheism is the product of a diseased organism he had missed his usual morning coffee.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Tom Shea, I was not planning to weigh in on this conversation at all until Tom Mellett wrote of Steiner’s seminal description of the three dilemmas involving body, soul, and spirit rejection, as seen with his lecture “How Do I Find the Christ”?

You see, there are several places where Steiner rather consistently went over this situation involving denial of God, rejection of Christ, and refusal of the Holy Spirit. So, I doubt that he ever missed his morning coffee, and maybe you would like to review these references over yours.

Building Stones for an Understanding of the Mystery of Golgotha, lecture III, April 10, 1917

Aspects of Human Evolution, Lecture II, June 5, 1917

How Do I Find the Christ?, October 18, 1918

The Mission of Archangel Michael, lecture IV, November 28, 1919

The Impulse of Renewal in Culture and Science, lecture VI, March 10, 1922

There is a great deal to show for this because it is both consistent and extends over some five years (1917-1922) in which Steiner felt it important to reiterate again. As well, since you gave something personal from your son, which I found remarkable, please allow me to say that I also know of someone who denied God, and it was because he suffered from heart disease. This was my father, who used to scream at his wife, who he knew was a Christian, “There is no God.” You see, he suffered from ill health for many years. He also suffered the effects of PTSD from WWII. He was a sailor in the Battle of Okinawa, which began on Easter Sunday, April 1, 1945.

LikeLike

Tomhartshea wrote:

“If you harbour the thought, ‘This person is ill’, simply because they express a point of view that you yourself believe to be wrong, is this respect?”

Your statement takes for granted that disrespect is the reason Steiner suggests atheism is an illness. But why assume disrespect is behind Steiner’s view? One could make an argument he was motivated by disrespect, but one cannot rightly just take it for granted, as you seem to do.

After all, couldn’t one turn the assumption around and assert that merely because you disagree with Steiner’s view that atheism is a kind of illness, you disrespect his view by assuming he could only have been motivated by disrespect? But what if Steiner came to his view not through any disrespect, but through direct observation? That is not impossible. What if Steiner actually observed and experienced what he meant by the word “God”? Then it would be natural for him to look into the question of why some are blind to “God.”

A complication here is that the “God” and the “atheism” Steiner refers to are rather different from “God” and “atheism” as often imagined. The often-imagined God is a merely theoretical being who supposedly controls everything that happens and possesses attributes that arguably are absurd and leave no space for human freedom. The “God” and thus the “atheism” to which Steiner refers does not have those absurd attributes and is not merely theoretical, but can rather be experienced.

Steiner’s view would only be regrettable, I suggest, if he also believed his view should be privileged by the state or that atheists should be penalized in some way by the state. But of course Steiner thought no such thing and on the contrary believed that making the state the arbiter of such things would have been monstrous. He was intensely libertarian with respect to cultural freedom, freedom of thought and belief, etc.

LikeLike

To complete Steiner’s aphorism:

Atheism or denying the Father-principle (denying pre-existence) is an illness of the soul, denying Jesus or Christ is misfortune of the soul and denying the spirit (denying afterlife) is self-deception.

Human freedom is possible thanks to our inclination to evil, greed and cruelty.

LikeLiked by 2 people

Wow, Anthony the Great of the Netherlands! I am quite surprised to see such an egregious error in your citing of what Rudolf Steiner actually said about atheism! This is important here because you are giving a quite misleading answer to Tom Hart Shea, who specifically reacted to Steiner’s dictum that to be an atheist is a disease of the physical body itself, not just some dereliction in the soul.

I quote from the following lecture How do I find the Christ?

16 Oct 1918, Zürich, GA 182

(The emphases are mine.)

https://wn.rsarchive.org/Lectures/19181016p01.html

“Spiritual Science shows us that in every case where a man denies the Father God — that is to say, a Divine Principle in the world such as is acknowledged, for example, in the Hebrew religion — in every such case there is an actual physical defect, a physical sickness, a physical flaw in the body.

To be an atheist means to the spiritual scientist to be sick in some respect. It is not, of course, a sickness which doctors cure — indeed they themselves very often suffer from it — neither is it recognised by modern medicine … but Spiritual Science finds that there is an actual sickness in a man who denies what he should be able to feel, in this case, not through his soul-nature but through his actual bodily constitution.

If he denies that which gives him a healthy bodily feeling, namely that the world is pervaded by Divinity, then, according to Spiritual Science, he is a sick man, sick in body.

====

Ton, you go on to state correctly that not finding the Christ is a misfortune of soul, but when you speak of self-deception in denying the spirit, you are again interpreting Steiner your own way. I would like to provide the exact words Steiner said for the sake of Tom Hart Shea, since Steiner was actually rather insulting of those who deny the spirit, and THS needs to see the exact words. Stay tuned.

LikeLiked by 1 person

To continue with Steiner’s progression of Body (Father-God), Soul (Son-God) and Spirit (Holy Spirit), I copy from the lecture

https://wn.rsarchive.org/Lectures/19181016p01.html

as translated by AP Shepherd and Dorothy Osmond in mid 20 C.

I will provide key German words with more synonyms as well as my own translation of the last sentence, which restores Steiner’s typically blunt assessment that gets a bit diluted by the translators.

———

“There are also many who deny the Christ. Spiritual Science regards the denial of the Christ as something that is essentially a matter of destiny and concerns man’s soul-life.

To deny God is a sickness; (Krankheit= disease

to deny the Christ is a calamity. (Unglück=misfortune, disaster, tragedy, accident — literally “bad luck”)

This must inevitably be the view of Spiritual Science. To be able to find Christ is a matter of destiny, a factor that must inevitably play into the karma of a man. To have no relationship with Christ is a calamity.

To deny the Spirit, the Holy Spirit, signifies dullness, obtuseness, (Stumpfheit=stupidity) of a man’s own spirit. The human being consists of body, soul and spirit; in all three there may be a defect.

[1] Atheism — denial of the Divine — denotes an actual pathological defect.

[2] Failure to find in life that link with the world which enables us to recognise the Christ, is a calamity for the soul.

[3] To be unable to find the Spirit in one’s own inmost being denotes obtuseness, a kind of spiritual mental deficiency, though in a subtle and unacknowledged form.”

—————

Now the German text of the last sentence:

Den Geist in seinem eigenen Inneren nicht finden können, ist eine Stumpfheit, in gewissem Sinne ein Idiotismus, wenn auch ein feinerer und wiederum eben nicht anerkannter Idiotismus.

My translation:

“Not being able to find the spirit within yourself is a stupidity, in a certain sense an idiocy, albeit a more subtle thus unacknowledged idiocy.”

Idiotismus = “idiotism” – archaic way of saying “idiocy”

Stumpfheit = “dullness, obtuseness, stupidity”

LikeLike

In Steiner’s time, “idiocy” had a different meaning from what it means today, no? Wasn’t it in his time a medical term for something like mental retardation? In any case, it may be worth emphasizing that Steiner uses the qualifying phrase: “in a certain sense”.

LikeLike

Tom, my Steiner quote was from a year earlier (1917):

“To be an atheist is possible only for those who are wholly insensitive to the phenomena of external nature. For if the physical forces in us are not blunted, we are continually aware of the presence of God. Atheism is really sickness of the soul, a disease of the human personality.” GA0175/19170410

To Steiner the Father-God was a hidden God (Deus absconditus):

“He could be called ’a hidden God’… For God is not there for your senses or intellect, which explain material perceptions. God is magically concealed in the world. And you need His own force in order to find Him. This force you must awaken within yourself. Etc.” GA008_c02

LikeLiked by 1 person

So, Ton, you didn’t make a mistake at all! Rudolf Steiner did! Well, that’s a great relief! Your perfect record is still intact.

LikeLike

Steiner actually improved on his renderings concerning atheism being a sickness of the body, denial of Christ being a calamity of the soul, and rejection of the holy spirit being a destructive self-denial in these several lectures from 1917 to 1922. It shows that he grew to the realization of the scope of the situation. I wrote to Shea about these points of interest, but maybe they will appear now.

LikeLiked by 1 person

The atheism-theme is connected with Aristotle’s philosophy. Steiner’s Aristotle teacher, Franz Brentano, had died in March 1917 (cf. Riddles of the Soul, CW 21).

‘Atheism‘ in: http://www.rudolf-steiner-handbuch.de/images/SteinerHandbook2015.pdf

LikeLiked by 1 person

What was Aristotle’s conception of the human soul?

“When an individual incarnates he owes his physical existence to his father and mother. But he owes only his physical inheritance to his parents. The whole man, according to Aristotle, could never come into being solely through the union of father and mother, for this whole man is endowed with a soul. Now one part of the soul — let us remember that Aristotle distinguishes two parts of the soul — is tied to the physical body, expresses itself through the body and apprehends the external world through sense-perception. This part of the soul arises as a necessary by-product of man’s parental inheritance. The spiritual part of the soul, on the other hand, the “Active Reason” as Aristotle calls it which participates through intellection in the spiritual life of the Universe, in the “nous”, is immaterial and immortal and could never come into being through parental inheritance, but solely through the participation of God — or the “Divine” as Aristotle calls it — in the procreation of man through the parents.

It is thus that the whole man comes into existence. The whole man is born of the co-operation of God with the father and mother, and it is most important to realize that Aristotle understands the word “man” in this sense. From God man receives his spiritual soul or “Active Reason” as Aristotle calls it. This “Active Reason” which comes into being with each individual through Divine co-operation, evolves during life between birth and death. When man passes through the gate of death the physical body is given over to the Earth, and, with the body, the lower part of the soul, the “Passive Reason” in Aristotelian terminology, which is associated with the physical organism. The spiritual part of the soul, the “Active Reason”, on the other hand, subsists according to Aristotle, and when “separated, appears just as it is”, withdraws to a world remote from the phenomenal world and enjoys immortality. Now this immortal life is such that the man who performed good deeds whilst in the body is able to look back upon the fruits of his good deeds, but cannot change the karma of his past actions. We only understand Aristotle aright when we interpret his ideas as implying that through all eternity the soul looks back on the good or evil it has wrought.”

GA175, lecture 2, 3 April 1917.

Thus, Aristotle accepts immortality of the individual soul-spirit after death, but rejects reincarnation. How can that be?

LikeLike

Ton, I think it would be more correct to say that human freedom is possible thanks to our inclination to ‘overcome’ evil, greed and cruelty.

These words from lecture VIII of the Apocalypse of St, John are pertinent:

“Do not consider it a hard thing in the plan of creation, as something which should be altered, that humanity will be divided into those who will stand on the right and those who will stand on the left; consider it rather as something that is wise in the highest degree in the plan of creation. Consider that through the evil separating from the good, the good will receive its greatest strengthening. For after the great War of All against All, the good will have to make every possible effort to rescue the evil during the period in which this will still be possible. This will not merely be a work of education such as exists to-day, but occult forces will co-operate. For in this next great epoch men will understand how to set occult forces in motion. The good will have the task of working upon their brothers of the evil movement. Everything is prepared beforehand in the hidden occult movements, but the deepest of all occult cosmic currents is the least understood. The movement which is preparing for this, says the following to its pupils: “Men speak of good and evil, but they do not know that it is necessary in the great plan that evil, too, should come to its peals, in order that those who have to overcome it should, in the very overcoming of evil, so use their force that a still greater good results from it.”

https://wn.rsarchive.org/Lectures/GA104/English/APC1958/19080625p01.html

LikeLiked by 2 people

Or is freedom possible thanks to the overcoming of our inclination to evil? When we already have an inclination to overcome, there is no real freedom.

Cf. evil inclinations in Steiner GA0185/19181026, and wiki/Concupiscence and wiki/yetzer hara

LikeLike

I am very grateful to Tom and Ton for seeking to bring clarity to what Steiner said about Atheism. What has been brought does not ease my discomfort and I still feel that these remarks were a mistake on Steiner’s part. I feel it is a regressive way of thinking, like the stereotypes he offered to characterise folk-souls. I guess this is simply one of the things I will have to live with, balanced by the things he said which have sustained me spiritually for many years, and maybe one day I will understand why he made these remarks.

If Steiner had said that thinking atheistically CAN make one physically ill, that failure to recognise The Christ at work in the world CAN be a calamity for the soul, and that being unable to find the Spirit in one’s inmost being CAN lead to a stupidity, a kind of subtle idiocy, then I feel I would have been able to appreciate those as insights into how certain thoughts and experiences and mental attitudes CAN be detrimental/tragic /stumbling blocks for human beings.

I also want to apologise to Jeremy for derailing the discussion, which was originally about the afterlife.

For myself, in answer to the question, ‘Do you believe in an afterlife?’, I would say, as Jeremy offered ,“Yes I do, and also in many ‘before’ lives as well as afterlives to come”.

Lets all meet at 12 noon under the Kremlin clock on September 29th 2319.

LikeLiked by 2 people

No need to apologise, Tom, this has been a worthwhile diversion!

LikeLiked by 2 people

Yes, and it certainly raises a threefold question about a person who does not believe in an afterlife. Is it due to a physical defect? A soul misfortune? Or spiritual idiocy?

Even more: there are many people who believe in an afterlife, but not in a “beforelife.” Seems to be a lesser defect than rejecting both ends of life.

LikeLike

My two cents:

Steiner often makes unequivocal statements that he does not mean absolutely unequivocally. He balances unequivocal statement in his work in at least a couple of different ways. First, when he makes one unequivocal statement, one can often find him elsewhere making a very different, partly contradictory statement. The two statements do not actually cancel each other out but rather are intended to balance one another and to gently prod the reader’s thought a little beyond an absolutely literal approach to language. To me that is one of the biggest and most difficult things to perceive in Steiner: in his speech he often plies a spectrum between the extremes of literal and figurative, rather than entirely separating those two extremes. Art and science fuse in revolutionary ways in his work. His seemingly “literal” statements are often actually figurative statements that seek to approach literalness as closely as possible rather than arrive there. Literal statements in a sense require only very limited mental activity on our part. Figurative statements are to some extent always a metamorphic process that we must re-enact within.

Steiner as I understand him teaches that when it comes to deeper realities, one proceeds by a neverending process of thesis, antithesis, synthesis, and that the resulting synthesis becomes a new thesis then confronted by a new antithesis and then again a new synthesis, ad infinitum. Of course he rarely explains all that abstractly in, say Hegelian fashion, but that way of looking at things is implicit in all his thinking. Polarity, where opposite poles in some sense contain each other, is fundamental. No single statement we can make about reality is ever completely adequate to it. No statement, taken absolutely literally, is true. The only exception would be with the use of artificial symbol systems that start from unquestioned simplifying assumptions, such as A=A, or with perfectly clear, but invented entities, such as points, lines, and planes, so that then one can make absolutely precise statements because one has decided in advance by a kind of fiat to assume that set of precise logical entities, though nothing in reality perfectly corresponds to such statements. The mineral world approximates most closely to such artificially purified logic, but even the mineral world bursts those bonds at various points. Logic that does not incorporate polarity materializes thought, recreates thought in the image of matter, and thought can then serve as a tool for the building of machines, the creation of technology, and the manipulation and control, to some extent, of matter.

Though Steiner often favors unequivocal forms of rhetoric even when speaking of this or that being of the spiritual world, he also repeatedly points out in various ways, sometimes by barely noticeable turns of phrase, that no single point of view or statement is complete, and that every point of view must be corrected by others.

And above all think what it would have meant if Steiner had constantly hedged every single definite statement with qualifications. Two results would likely have followed: 1) he might have appealed only to lawyers and philosophers, whereas he also wanted to appeal to scientists as well as non-intellectuals. And 2) he might have undermined the feeling that reason can say anything meaningful. Perhaps, through his acquaintance with the non-compos-mentis Nietzsche and with Nietzsche’s works, Steiner saw the danger that reason could be reduced to paradox and to constant self-interruption, and saw also how Nietzsche’s approach would grow into intellectual movements such as Deconstruction, movements that at times make it seem impossible really to say anything. If Steiner had constantly hedged statements, he would have been over-emphasizing paradox, which in one of his lectures (as I recall) he associates with Ahriman.

LikeLike

The problem with the belief in re-incarnation is that it is not possible to have re-incarnated from humans. One might believe in re-incarnation from other non-human living beings, or other universes, but not from other humans.

It is a simple math issue: humankind has been growing exponentially – There are way more humans in the last 300 years (or so) than in the rest of humankind existance before combined(!)

Most of us would have to be new souls or coming from animals/plants or other universes.

By nature of math and human evolutionary history only a very limited few could have had incarnated, in the past in another human being.

LikeLike

According to the BBC, 107 billion human beings have existed. Currently there are, what? 7 billion?

The magazine Scientific American puts the number of those who have ever lived at about 100 billion.

So I don’t see a math problem.

LikeLike

Thanks eduardo. This has had me worried for ages, well since I looked at population graphs. However, there is a big BUT- because of the recycling rate question. I love R:S. s 1400 year double cycle with one male and one female incarnation (When did he say that- I am hopeless at remembering chapter and verse). However THAT recycling rate does not fit the population growth curve.

My mother considered the gender alternatives and the whole ‘theory’- (because it can only or barely be considered a theory because it cannot be disproved- so perhaps an ‘article of faith’). Whatever, Mum saw reincarnation and karma as the answer to social injustice. So she could give up carrying the banner in Labour Party parades in the 1920s.(Applied Anthroposophy!)

In that scenario the current mysogyny and violence against women could be seen as some sort of karmic vengeance. I don’t like that idea at all, thank you, but my emotional rejection does not invalidate the idea.

On the other hand without belief in reincarnation and karma my life would be meaningless. And all those Angels in Eternity making sure that all the billions of life threads cross at the right moments and so leading me to situations where I have the free choice to make karmically positive decisions.

If that is not true why am I paying subs to the ASinGB?

LikeLike

As I recall, RS allowed that when bad things happen to people, it is not always karma. It may be something new, instead, and RS suggested it would then be balanced and made up for in the future. Steiner also allowed, if I’m not mistaken, that some things really do happen by chance (see Chance, Providence, and Necessity). But again, what happens by chance may in future be balanced by karma in some way.

LikeLike

Well Jeremy, you’ve gotten some responses from “across the Pond.” Now here’s one from “across the Channel” — by Michael Eggert in Düsseldorf.

He highlighted your blogpost in his Facebook Group called “No Bullshit Anthropsophie.” Here is my quick translation of his assessment and I’ll spare you the German:

==============

“How do you feel personally about life after death? This is how Jeremy Smith formulates the “Gretchen question” in his Anthropopper blog. He answers it briefly by saying that he believes we exist both before and after our present lives, but then he quickly hedges with responses from other people:

He cites a writer who believes in the continued existence of her books, and then C.G. Jung, who made do with his “eternal collective soul” idea. Smith more or less emphasizes his own faith in Rudolf Steiner’s competence in such questions and thus palms off the further answers onto Steiner — which does not seem all that courageous — and thus appears quite conventional for anthroposophists. Unfortunately, Smith avoids his own theory of knowledge — so the question is left hanging: in what or in whom does he (or anyone) believe?”

LikeLike

Tom, if Michael Eggert thinks that the question of my personal beliefs has been left hanging, then he has not read the post I wrote in 2015 in response to a similar question from Alicia Hamberg:

https://anthropopper.wordpress.com/2015/08/23/a-personal-credo/

What interests me, however, is what you yourself believe in. I’ve asked you this before and you’ve never answered. We know you are a lapsed Catholic and a lapsed anthroposophist and latterly you have been a worshipper at the feet of Der Staudi – but whether that amounts to anything that could be called a belief system you have not yet revealed.

LikeLiked by 1 person

I think we will all have our own unique inner thought journey regarding whether we believe in an afterlife. Jeremy’s post has prompted me to try and piece together the stages and events concerned in my own struggle with this question. Sometimes, particular episodes can play a key role, and going back to Jung, and his absolute certainty, I think that his near-death experience may well have been a very significant milestone leading to this conviction.

Here is a slightly edited account of this from

http://whitecrowbooks.com/features/page/how_a_near-death_experience_transformed_carl_jungs_attitude_to_mysticism

“On 11 February 1944, the 68-year-old Carl Gustav Jung slipped on some ice and broke his fibula. Ten days later, in hospital, he suffered a myocardial infarction caused by embolisms from his immobilised leg. Treated with oxygen and camphor, he lost consciousness and had a near-death and out-of-the-body experience . He found himself floating 1,000 miles above the Earth. Seas and continents shimmered in blue light and Jung could make out the Arabian desert and snow-tipped Himalayas. He felt he was about to leave orbit, but then, turning to the south, a huge black monolith came into view. It was a kind of temple, and at the entrance Jung saw a Hindu sitting in a lotus pos¬ition. Within, innumerable candles flickered, and he felt that the “whole phantasmagoria of earthly existence” was being stripped away. It wasn’t pleasant, and what remained was an “essential Jung”, the core of his experiences. He knew that inside the temple the mystery of his existence, of his purpose in life, would be answered. He was about to cross the threshold when he saw, rising up from Europe far below, the image of his doctor in the archetypal form of the King of Kos, the island site of the temple of Asclepius, Greek god of medicine. He told Jung that his departure was premature; many were demanding his return and he, the King, was there to ferry him back. When Jung heard this, he was immensely disappointed, and almost immediately, the vision ended. He experienced the reluctance to live that many who have been ‘brought back’ encounter, but what troubled him most was seeing his doctor in his archetypal form. He knew this meant that the physician had sacrificed his own life to save Jung’s. On 4 April 1944 – Jung sat up in bed for the first time since his heart attack. On the same day, his doctor came down with septicæmia and took to his bed. He never left it, and died a few days later.

More recently, thousands of people have experienced near-death experiences that frequently change their lives dramatically due to their impact, and more recent surveys (e.g. in Canada) https://nationalpost.com/news/canada/millennials-do-you-believe-in-life-after-life

Show that 66% of all those polled, and 70% of “millenials” believe in a life after death.

Maybe the natural loosening of the etheric body which RS predicted, and which would make the perception of Christ in the etheric realm from the 1930s onward is starting to turn the tide ?

LikeLike

One can also interpret Jung’s 1944 vision as a pre-birth experience made conscious by his heart attack. His archetypical vision was a reason to believe in a pre-life.

Jung’s account On life after death in: Memories, dreams, reflections (1961), google w6vUgN16x6EC, p.299 f. and on reincarnation p.319 (his complete ‘1944 vision’ in: The Book of Heaven, google aMNMAgAAQBAJ)

LikeLike

I agree with midnight rambler’s opening sentence. I think the question of ‘afterlife’ (and beforelife) arises in the context of ones own existential struggle. The account of Jung’s near-death experience exemplifies this very well. Despite the fact that I said Jung was ‘bullshitting’ earlier in this thread, I have great respect for him as an interpreter of the human soul. I was taking issue with his use of the word to ‘know’ in this context of a public discussion of ‘belief’ in an afterlife.

For myself, I can remember exactly when, as an adult, I finally believed that re-incarnation was something real. `for me this came about through contemplating life and its significance over many years , not through any ‘memories’, or visionary experiences, but through always yearning to know the significance/the meaning of my life.

LikeLiked by 2 people

I know that I have had experiences that prove that pre-existence before birth is real, as well as a near-death experience in which I felt close to crossing the threshold as accepted and without blame. These events occurred between my eighth and eleventh year. So, I often think these days about attesting to both the fact of eternity before birth, and immortality after death. The life-review after these many years is, indeed, a very worthwhile endeavour, and helps connect the dots with the karmic consequences that spiritual-scientific study helps open the door to consideration. Without it, what would be possible in terms of truth and knowledge?

Now, it seems very possible to consider that we humans are in the process of making the ‘flesh into word’, over these last two thousands years, since the “Word Was Made Flesh”, and dwelt among us with the entry of Christ into earth evolution. The Mystery of Golgotha does seem to be the necessary pivot-point in declaring the redemption and resurrection of humanity at its lowest point of descent. So, by now, it seems reasonable that personal events in which this ‘flesh made word’, are occurring on a rather routine basis, and even without spiritual-scientific study. For example, Carl Jung’s near-death experience made him convinced on a knowing basis concerning God, and immortality, and the eternity of the human quest. At least, that is what he personally attested to, and freedom proves that he gets to say his piece. This means a lot.

LikeLike

What or who is an atheist?

Someone who makes a cross in a questionnaire? Someone who fears to be ridiculed by the overwhelming public opinion, modern science if he believes in something supernatural?

Are Buddhists atheist, since Buddhism dismisses the idea of a God? Are there no atheists in Saudi Arabia, because apostasy is punished by death penalty?

In a survey in Germany more people „believed“ in angles than in God? Is someone who believes in angles but not in God is he/she an atheist?

How can a modern scientist who only believes in matter, physics, chemistry etc. be a non-atheist?

I think Richards Dawkins is one of the few who really thought through (or to the end?) his scientific ideas and who dared to speak them out?

Ottmar

LikeLike

Dear All:

What an array of responses! This seems to be a very fruitful topic for us. I’d like to share my story. I think I know something of why we go down so many pathways in facing with this question. When I was 4 or 5 years old I had an experience that triggered an existential crisis with which I still struggle at 73 years old. I was in the living room of my grandmother’s house watching the rest of the family sitting around the dining room table. Suddenly I felt a visceral sense of infinite distance between me and my surroundings. I “knew” there weren’t really tables and chairs and separate people, etc. It was all something else I’d never seen before! Nothing was separate. Everything was infinitely far away and intimately close at the same time. And I felt utterly and infinitely loved: I “belonged” to it! I knew the world I thought was real just a moment before was just a sort of veneer of what was really going on. I knew that we were “making up” our lives and surroundings. My child’s mind thought the grownups would be so happy to know I “got it” – I thought I’d be praised for learning it. My child’s mind/language could only manage: “Mommy, it’s a dream!” And my Mom said: “You’re sleepy. We’ll be going home soon”. And I realized she didn’t see and I viscerally felt like I was falling. And the experience ended.

My conscious thought was that some terrible mistake had been made. I was in the wrong place with the wrong people. I didn’t understand, of course, that I was making an unconscious choice to believe my own experience over what others thought. I know now that the majority of us start denying what we already know at a very early age. (Maslow says we all have what he called “peak experiences” – perhaps, continuously – but we keep ourselves unconscious of them out of fear) The fear for me was: if I believe my mother, I keep my safe life – the known – and my grandma’s house where I had her cakes and the fireplace, etc. But I made a choice to believe my experience and from then on nothing felt warm and secure to me ever again. I particularly remember how drab my Grandma’s house seemed from that moment. When I was a few years older and in school I encountered the concept of being kidnapped and thought that was what must have happened to me. And to this day I can feel like an impostor in this world. And I think we are all impostors – when we think with our finite minds instead of standing in the deeper inner “observer” – the “I” that’s “behind” everything we are.

I found Rudolf Steiner in my early 20’s – thank God – and then a profession where I could put my lived experiences to work – where I can use my awareness to help others. So my response to “Do you believe in an afterlife?” : how can spiritual substance be conveyed in words grounded in materialism?. They’re too puny to get at the heart of it. If we think of “life” as a thing and “after” as something in time we’re chasing our own tails. We need more than belief – we need experience and courage. I grew up in New York and here’s something you would typically hear when you asked a New Yorker for directions: “You can’t get there from here – first you gotta go somewhere else.”

LikeLike

Hi Jeremy,

It’s great to listen to these psychologists/researchers challenging the ‘mainstream’ view that the human being is just a physical body…

I wonder if the anthroposophical society could tackle the question in a similar way, a live filmed event with guest speakers, doctors, priests etc. There is a hunger for knowledge, especially to your question…

LikeLike

To me, Jung is nothing compared with Steiner. Or perhaps like the moon compared to the Sun.

One reason people object to those who say they “know” God is that the objectors assume a certain set of arguably bad theological definitions of God — for example, that “God” means a being who is omnipotent and omniscient and controls everything. While I think I have known God at times in my life, I mean by “God” an ever new, ever creative love and life at the transcendent spiritual foundation of all existence — but not an omnipotent or omniscient being. Omnipotence and omniscience would seem to entail entire absence of human freedom. If, for example, God knows in advance the outcome of all my decision processes, then they are not real decision processes, are they? If the outcome is determined in advance? But if those decision processes are profound enough and real enough, then God cannot know the outcome — what I will decide — in advance, and in that sense God is not omniscient. Further, if God is omnipotent, then God controls everything I do and again, I have no freedom, no real power of decision. I seem to recall that Steiner attributes something resembling omniscience to the demonic side, not to God. Alfred North Whitehead and Charles Hartshorne also argued for the existence of God but against the existence of divine omniscience or omnipotence.

LikeLike

I’ll add that Hartshorne, as I recall, says there is nothing in the Bible that really requires the interpretation that God is omniscient or omnipotent. I gather those characterizations of the biblical God were introduced by medieval theologians. And is there not a scene in the Bible where Abraham or Moses or someone argues against something God wants to do, and causes God to change course? That does not immediately suggest divine omniscience or omnipotence.

The “God” to which many atheists strenuously object is the theorized omnipotent, omniscient one. It does not occur to many of these atheists that “God” need not be thought of in that way and that minus those two attributes, can to some extent actually be experienced.

LikeLike

Another bit of data: There’s a somewhat recent book out there that claims to take a representative sample of famous atheists and theists from the course of history. The book then looks at the relationships these people had to their fathers and comes to the conclusion that the famous atheists often had traumatic relationships or non-relationships with their fathers, while the famous theists had loving relationships with their fathers.

I have no idea if the book is well founded statistically or scientifically. If its thesis is correct, however, and if the pattern it claims to find holds up, that would seem to mean that trauma often plays a role in the genesis of elaborated atheistic views.

LikeLike

I wonder if anyone is still looking at this in November. Being about old enough (77) to stand for election as POTUS , I forgot how to log in to blog for several months.

Whatever, The original article was: ‘Do you believe in afterlife’. Some of the comments seem rather more elaborate than : YES or NO.

My own response is : Praps?,

However, I found this quotation from Carl Rodgers in ‘The Carl Rodgers Reader’ one I can sympathise with.

“All these experiences, so briefly suggested rather than described, have made me much more open to the possibility of the continuation of the individual human spirit, something I had never before believed possible. These experiences have left me very much interested in all types of paranormal phenomena. They have quite changed my understanding of the process of dying.

I now consider it possible that each of us is a continuing spiritual essence, lasting over time, and occasionally incarnated in a human body.”

The context in which this ‘conversion’ took place was what it was. However, the last sentence sums up my answer to the question in the title.

Of course this is part of my consideration of : Faith, Belief and Knowledge.

OH! and 20 years ago I was VERY ill and put into a coma for a month. To my great disappointment there was NO light at the end of the tunnel, NO angels. Perhaps I wasn’t nearly dead enough.

LikeLike